Listen to this article in Afrikaans:

How Syntropic Farming Changed A Karoo Farmer’s Future

You’re on a farm in the Karoo. Sheep outnumber the edible plants and what you’re actually harvesting is dust.

What is a budding veggie farmer to do? If you are Cornel Strydom, you get on a plane to Spain to meet a Swiss biologist. Wait, let us explain.

How It Started

On their farm, Nagtegaalsfontein in the Karoo, Cornel Strydom describes the climate as cold, dry and arid with a short rainy season and no way of implementing traditional South African agriculture techniques.

Faced with these challenges, in true adaptive Saffa fashion, she embarked on finding a solution and completed a permaculture design course in 2018. Her factfinding also lead her to a farm in Spain where she was fortunate enough to meet her syntropic farming mentor, and the man who coined the term, Ernst Götsch.

There, Cornel learned how to apply syntropic farming techniques in a Mediterranean climate, which would be the starting point of transforming Nagtegaalsfontein, a fine-wool Marino sheep farm of 3000 ha. With Cornel’s hard work, 2000 m2 of the farm has been converted into a syntropic system.

Who Is Ernst Götsch?

Ernst Götsch, born in 1948 in Raperswilen, turned his back on creating GMOs in a Swiss laboratory to answer the burning question:

“Wouldn’t we achieve greater results if we sought ways of cultivation that favour the development of plants, rather than creating genotypes that support the bad conditions we impose on them?”

He developed and perfected the art of syntropic agriculture in many different climates such as Namibia and Costa Rica, but his crowning achievement was the complete restoration of his cocoa farm in Brazil.

It proved that by allowing nature to thrive, all the systems that we as humans break down will restore themselves.

Error, group does not exist! Check your syntax! (ID: 20)

So, What Is Syntropic Agriculture Anyway?

In essence, syntropic farming produces food while restoring and managing ecosystems. The plants, insects and animals all naturally want to work together to help each other thrive.

By working according to syntropic principles, you won’t just be able to produce food, but also restore the land as you go.

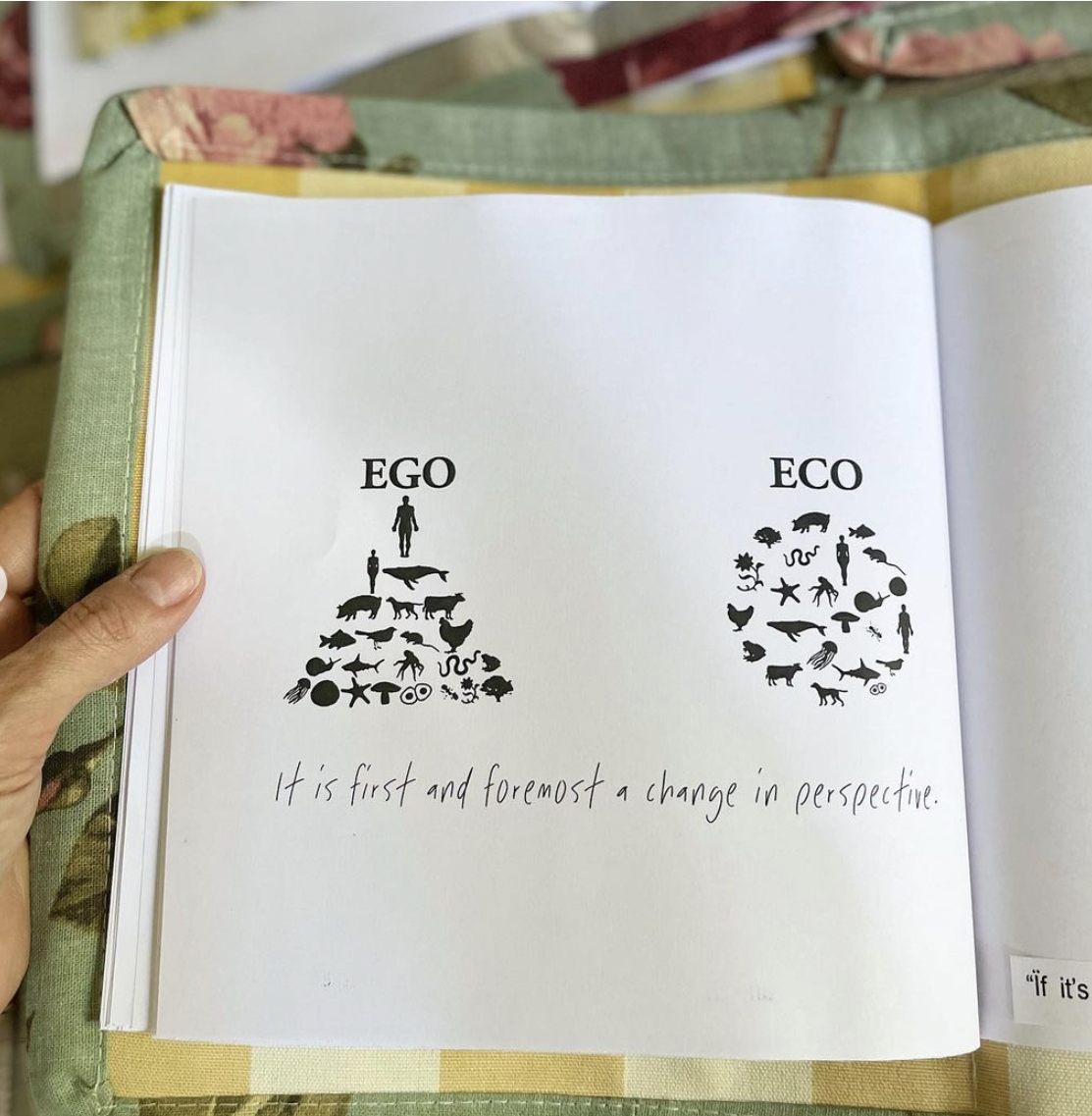

Cornel says: “Syntropic agriculture is a change in perspective. You have to wipe the slate clean and look at nature through the eyes of a child.”

She insists that she is no farmer, but rather a vegetable gardener: “I see myself more as a tool for nature. Nature already knows the perfect way to create forests.”

Syntropic basics

Cornel says that you have to imagine that you are planting in time and in space.

In one piece of land, you will not only plant seeds that are able to be harvested in three weeks, but right next to those seeds you will plant trees that will be in the system for upwards of 80 years.

Plants that support each other are grown together, meaning there is no competition and no need for weeding or pesticides. Weeding becomes a harvest.

Search our HOMEMAKERS SUPPLIERS

Syntropic Farming Is Like An Onion

When we sat down to get to know Cornel a little bit better, she was happy to answer the many questions we threw her way.

How do you find inspiration to improve or adjust your practices?

“Syntropic farming is like an onion with layers. As soon as you uncover one layer it leads to more. You learn from each project, each plant, each week. You need to observe and act on your observation. As you harvest radish and then lettuce, you make more space for cabbage or Brussels sprouts or spinach. You end up filling spaces that are empty. Nature wants the soil to be covered. And nature loves roots in the soil.”

She breaks it down by saying: “It’s a snowball effect. As you plant, you learn. “

What is the most unexpected lesson you have learnt from this syntropic farming journey?

“In nature, there’s only unconditional love and cooperation. We think there is strife and competition, but plants cooperate. If you put a tree seed in the soil, you’re well-advised to plant an aloe or prickly pear or fennel next to it, because they’re prepared to share water from their roots with this seed when there’s not enough for everyone.”

Cornel continues: “When you prune trees, they release gibberellic acid which is a hormone, through the root web that tells everything to start growing. We always prune when we plant, it inspires growth.” This permaculture technique is humorously referred to as “chop-n-drop”.

Error, group does not exist! Check your syntax! (ID: 20)

Error, group does not exist! Check your syntax! (ID: 20)

What is your favourite crop that immediately helps if plants are not doing well?

“Coriander, radish, peas, beans. Coriander is fantastic. It’s an amazing thing to energise your system. Sow them 5cm apart, prune something close by and sow in a straight line. Coriander inspires other plants to grow.” Cornel also loves the way that radishes can get a hesitant crop going: “Radishes are cheerleaders!”

What do you find less enjoyable about the farming experience?

With a sigh, she admits: “Black frost and frost. Drought. Difficult conditions. You work your butt off and then it looks like everything dies in winter and then you have to start again.”

But, it’s not all bad news. Cornel is quick to emphasise: “Every season I learn something. You have to be flexible and never give up. If something dies, plant something else, don’t give up. Learn plant propagation techniques. Many plants will grow from cuttings.”

Do you believe that some people just have a green thumb? Why or why not?

“You won’t know if you have a green thumb if you don’t plant something.”

Cornel is not really a fan of pot plants: “Pot plants don’t count. If your pot plants die, it does not reflect on whether or not you have a green thumb. Pot plants are plants in prison.”

She believes that in planting and making plants thrive: “Consistency is key.”

What would you want anyone embarking on a syntropic farming journey to know before they start?

“Just change your perspective.”

“You’re going to plant a lot of plants close together. Give nature a chance to show it what it’s capable of.”

She also emphasises: “You’re not going to eat everything that you plant. You have to accept that you’re going to plant things that are to the benefit of all, not just to you. We become more giving when we plant in this way. We become less attached. It brings back insects to the place we plant. We’re not going to fight nature.”

Cornel doesn’t believe in using pesticides: “We want insects because we want birds. We want to be involved in creating abundance.”

Error, group does not exist! Check your syntax! (ID: 20)

What are your future plans personally and for Nagtegaalsfontein?

Cornel Strydom and her friend Henda Lombaard started Seed Sisters. “We install vegetable gardens for clients using syntropic principles.”

“The thing that is the most mind-blowing is that clients think you install and then harvest and that there’s no more work. The reality is that you need to spend a minimum of 10 minutes a day in your veggie garden. It’s about consistency.”

“Veggie gardens look like they’re airy-fairy, but you need the discipline to grow vegetables. It’s spiritual. It’s good for your soul. You need to be available. It’s a long-term relationship.”

And for Nagtegaalsfontein? “I would like to plant a lot of trees as food for animals and humans. The plan is to plant 500 ha of different trees that support each other and love the area. This will result in creating a micro-climate. We’re also going to build a greenhouse for workshops and a growing space, especially for lemon trees. The growing space will be built to do plant propagation and season extension.”

What is the one takeaway you wish our readers to get from this article?

Cornel believes that everyone lamenting the climate crisis should stop fuming and start farming.

“The climate we need to change is between our ears.”

In her own words: “Today is the perfect day to start growing some vegetables and trees.”

Thank you again to Cornel Strydom for her time, as well as the gorgeous images from her Instagram page.